| Location: | Duval County, Florida |

|---|---|

| Occupation Dates: | 1587-1702 (as mission site); earliest date of pre-Spanish Timucua settlement unknown |

| Excavator(s): | Martin Dickinson; Rebecca Douberly-Gorman; Charles Fairbanks; John Goggin; John Griffin; Barry Hart; William Jones; Lucy Wayne |

| Dates excavated: | 1951 (Goggin); 1955 (Griffin); 1961 (Jones); 1982 (Hart and Fairbanks); 1985 (Dickinson and Wayne); 2007-2008 (Douberly-Gorman) |

Overview

The Mission of San Juan del Puerto is located on Fort George Island, Florida. Believed to be the longest-lasting Spanish mission settlement, it was founded around 1587 and occupied until 1702 (Hann 1996:141; Worth 1998a:47). On November 5, 1702, Governor James Moore of South Carolina with his English militia and Indian allies attacked and burned the mission along with several of La Florida’s other mission settlements. San Juan del Puerto’s occupants, mainly comprised of Timucuan and Guale American Indians as well as a small number of Spaniards, either managed to escape and fled to St. Augustine, were killed, or were taken as prisoners (Hann 1996). According to mission censuses from 1736 to 1739, the mission was re-established under the name of San Juan del Puerto de Palica following the Yamasee War of 1715 (Dickinson and Wayne 1986; Worth 1998b:153-156). By the late 1750s, any remaining occupants of San Juan migrated to the mission Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe de Tolomato at St. Augustine to live among the Guale, where they likely remained until the Spanish ceded La Florida to the British in 1763 (Worth 1998b:153-156).

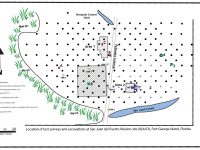

Fort George Island is in northeast Florida off the Atlantic coast. It is the southernmost island in a string of several islands that form a sea chain, extending from the Carolinas to Florida. Because the island is in an area of continuous active coastal change, it has undergone changes in size and shape over the past 400 years. The San Juan del Puerto mission site sits just north of a small tidal creek on the west side of the island. Situated approximately one mile north of the St. Johns River, the south and east portions of the site are in live oak hammock and the north and west portions are in planted pines (Dickinson 1989:396; Dickinson and Wayne 1985:2-1). Today, Palmetto Avenue runs along the mission site’s north/south axis, bisecting the site. A mosquito control ditch is located at the north end of Palmetto Avenue, just slightly west of the road, and San Juan Creek is situated near the south end of Palmetto Avenue to the east. It is bounded on the western edge by a marsh and on the eastern edge by a golf course. Following the mission period, the site area was within the boundaries of plantations that consumed the whole of Fort George Island, such as the Hazzard and Kingsley Plantations. Therefore, it was subsumed under the agricultural landscape from the late 18th to the mid-19th centuries. The land containing the site mostly recently was used in the 1960s to cultivate pine. The main damage to the site is in the southern portion, resulting from the dredging of the San Juan Creek for mosquito control (Dickinson 1989).

The San Juan del Puerto site was first identified by John Goggin in 1951. In the following years, the site underwent several surveys and excavations. Griffin initiated archaeological field work at the site in 1955, followed by more extensive excavations by William Jones (1967) in 1961. Griffin’s and Jones’ efforts resulted in the documentation of several mission related features. Jones identified the remains of what resembled a palisade north of San Juan Creek, as well as several individual shell middens that appeared to be the remains of domestic Indian dwellings on the west side of Palmetto Avenue. In 1982, Barry Hart and Charles Fairbanks carried out surveys that delineated the boundaries of the site to the east of Palmetto Avenue and identified concentrations of artifacts (Dickinson 1989). In 1985, Martin F. Dickinson and Lucy B. Wayne (1985) conducted additional surveys and three test unit excavations in order to fully delineate the boundaries of the site and to gather more sufficient data to satisfy the requirements for a proposed National Register of Historic Places nomination. These excavations revealed the core of the mission site, including a mission complex and an Indian village that encompassed about seven acres. They also documented the mission complex’s church, convento (friar’s quarters), cocina (kitchen), and cemetery.

Documentary Evidence

Several historic Spanish documents describe mission San Juan del Puerto. One San Juan’s most recognized Spanish Friars, Fray Francisco Prieto spent 33 years at the mission. He arrived at San Juan in 1595, roughly eight years following the mission’s founding (Hann 1996:141). Prieto recorded a wealth of ethnographic information regarding the Timucuan Indians living at the mission. His works include three catechisms in both the Timucuan and Castilian languages, a confessionario, and a documentation of Timucuan grammar (Hann 1996:122). Prieto created these booklets to aid the Spanish friars in Indian religious conversion. Other Spanish documents such as census lists, petitions, letters, and maps provide additional information regarding the mission. British archival collections also offer documentary evidence, such as Englishman Johnathan Dickinson’s journal. On his coastal journey to South Carolina following his shipwreck off the coast of south Florida, Dickinson described his 1697 visit to the mission, which he refers to as San Wans (Dickinson 1945:66-67). Later, American naturalist William Bartram wrote about the mission’s ruins during his visit to Hazzard’s plantation in 1765 (Dickinson 1989:398).

Excavation History, Procedure, and Methods

Four years after John Goggin’s identification of Mission San Juan del Puerto in 1951, John Griffin carried out limited testing and surface surveys that resulted in the recovery of mission period Spanish and Indian artifacts. Goggin and a group of volunteers excavated six 5 ft. (1.5 m) squares. Although the exact location of the squares is unknown, the group recovered Native American artifacts that included San Marcos and St. Johns pottery as well as historic artifacts such as Spanish Olive jar and majolica, glass, and miscellaneous iron fragments (Ashley and Douberly-Gorman 2021:13). In 1961, John Goggin and William Jones excavated more extensively, exposing 50 feet of a palisade wall that extended up from San Juan Creek and recovered a large quantity of artifacts including religious medals and San Marcos ceramics. As a result of these finds, they designated this area as the mission core. Jones also recovered a carved wooden war club from a spoil pile at the east end of the San Juan Creek and several sherds of Spanish majolica from the creek. After Palmetto Avenue was cleared for pine tree planting in the 1960s, Jones discovered and mapped a number of individual shell middens on the west side of the road, surmising that the middens were likely associated with the dwellings from the Indian village that would have likely surrounded the mission complex. A routine inspection of the site in 1981 documented logs exposed by erosion on the west side of Palmetto Avenue. As the wood appeared to be old and potentially associated with the mission, Jones submitted a sample for radiocarbon dating. It returned a date of A.D. 1480 ± 55years (Dickinson 1989:399). In 1982, Barry Hart and Charles Fairbanks conducted surveys as part of Florida’s land development process in order to delineate the boundaries of the site and identify any impacts the proposed development would have on the mission site. The survey consisted of a 25 m subsurface grid over the east side of Palmetto Avenue, where Jones had proposed the mission’s location. They also carried out a probe survey of a 75 m area west of Palmetto Avenue in an effort to locate mission-related Indian structures. These surveys indicated a probable structure and revealed that the mission site did not extend beyond 200 meters north of the creek (Dickinson 1989).

In 1985, excavations by Dickinson and Wayne sought out data for a proposed National Register of Historic Places nomination. They performed an extensive background search of historical sources and compiled data from previous archaeological investigations. Dickinson and Wayne (1985) conducted additional surveys that included 165 (25 x 50 cm) shovel tests, a soil resistivity test to locate any structural remains, and excavations of three 1 x 2 m test units taken down in 10 cm levels. All material from the shovel tests and test units was screened through ¼-inch mesh. Fieldwork began with the expansion of Hart’s and Fairbank’s 25 m shovel test grid in order to delineate boundaries of the site that had not yet been established. This was followed by the addition of additional test units to form a grid reduction of Hart’s and Fairbank’s 25 m grid to form a 17.5 m grid in the areas that contained the highest density of materials. In order to determine the most ideal areas to place and open the test units, they created various artifact density maps from the shovel test results based on specific classes and combinations of artifacts that included marine shell, San Marcos and St. John’s pottery, Spanish ceramics, and all other Indian pottery. Dickinson and Wayne (1985) used the density maps to identify an area with a much higher concentration of San Marcos pottery in the southern portion of the site than Jones had reported in his proposed mission core area to the north. In addition to these two larger areas defined by concentrations of Native American ceramics, three smaller areas were also identified that formed the “typical square core of the mission” (Dickinson, 1989:404). Within this square core, Dickinson and Wayne recovered the only concentration of Spanish pottery (majolicas and olive jar sherds) revealed at the site. This area is thought to represent the central core or center of Spanish activity at the mission site and revealed that limited use of Spanish materials occurred outside of the area of this core.

Soil resistivity tests were conducted in artifact concentrations, as well as the area where Jones had excavated the palisade. The site was divided into two areas. SR-Area 1, to the west of Palmetto Avenue, included the Spanish and San Marcos pottery concentrations; SR-Area 2, on the east side of the road, was located where Jones had documented the possible palisade. The tests revealed a probable group of structures in SR-Area 1. Any structural remains in Sr-Area 2 were ambiguous, although the testing did identify the palisade ditch reported by Jones (1967) (Dickinson 1989).

Dickinson and Wayne (1985) used the results of the artifact density and soil resistivity tests to determine placement of three test units, Units A, B, and C. Unit A was placed in the western portion of the site in order to intersect the Spanish and Native American artifact concentrations. It yielded mostly San Marcos pottery, a small quantity of majolica and olive jar sherds, and bone elements from several species of fauna and revealed two linear trenches. Unit B, placed in Area 2, contained human remains that appeared to be the secondary burials of multiple individuals, as well as Spanish and Native American pottery, daub, shell, and charcoal. Unit C was also placed in the concentration of Spanish and Native American artifacts in Area 1. Overall, six features were located in Unit C that included a midden feature, one square post and a possible square timber, two oval post holes, and a postmold, all of which are believed to be associated with a Spanish domestic structure (Dickinson and Wayne 1985; Dickinson 1989).

Rebecca Douberly-Gorman conducted the most recent excavations of the site during 2007 and 2008 University of Florida field schools (Ashley and Douberly-Gorman 2021). Focusing on assumptions made by previous archaeologists regarding the location of mission areas and buildings, field investigations focused on two primary locations, Dickinsion and Wayne’s designated SR-Area 1, including Unit C to the east, and SR-Area 2. Excavations also included two investigative units. One was placed in a shell heap in the far southwestern corner of the site, and the other approximately 100-m northeast of SR- Area 2, in a low shell mound. Overall, excavations comprised of fifty-eight 50 cm x 50 cm shovel tests, eight, 1 m x 2 m units, and one, 1 m x 1 m square. Fifty-three features were recorded, including postholes/molds, trenches, shell middens, refuse pits and burial pits. Using a comparative analysis approach based on other mission research, new and existing research of San Juan, and historical documents, investigations of the areas led to several new proposals regarding the mission complex. To begin, rather than the mission settlement being a tightly clustered community as what was previously suggested by earlier archaeological investigations, it was more a centralized mission complex with residential households covering the majority of the eastern half of the island. In addition, excavations also suggest that the location of the church was in the south end of Area SR-1 and to the southeast based on remnants of a clay floor and human remains. Investigations also suggest that the convento was located just to the north or northwest of the church. A probable location for a plaza area was identified between the convento and the church and the SR-2 Area is the likely location of the Native center, at least during the late mission period. In addition, it was determined that the palisade discovered by Jones in 1967 may not relate to the mission, but post-date to the plantation period (Ashley and Douberly-Gorman 2021).

Summary of Research and Analysis

The occupation of San Juan del Puerto dates from about 1587 to 1702 and it was re-established sometime after 1715, according to later mission censuses taken by the Spanish in St. Augustine. Over the course of several decades, surveys, soil resistivity testing, and excavations at the site have revealed that, similar to other contemporary mission settlements such as Mission San Luis de Apalachee in Tallahassee, San Juan del Puerto likely contained a church, convento, cocina, and a cemetery. In addition, a widespread Native American village community was part of the mission complex. Although the only located remains of Indian dwellings were the individual middens documented and mapped by Jones in the 1960s, all of the structures, including both Spanish and Native American, would have likely been of wattle and daub construction (Dickinson and Wayne 1986). The palisade that Jones documented (Dickinson 1989) is in need of further investigations to determine what it is and when it was built (Ashley and Douberly-Gorman 2021). Artifact concentrations exposed through shovel testing and excavations have revealed that the Spanish activity area or central core of the mission contained the majority of Spanish artifacts. The Native American village contained objects of European origin such as metal religious medallions, but overall Spanish artifacts were limited in number (Dickinson 1989).

Gifford Waters and Charles Cobb

Florida Museum of Natural History

University of Florida, Gainesville, FL

November 2021

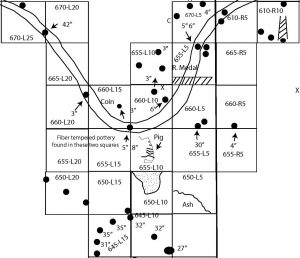

San Juan del Puerto was excavated using the English measuring system for the 1960s investigations supervised by William Jones. Units were excavated as 5-foot x 5-foot squares. Unit levels were typically 6 inches in depth. In the CMAP system, areas and depths of both units and features are recorded in feet. However, beginning and closing elevations in CMAP are recorded in inches, corresponding to the site excavation form recording system.

All maps are oriented with grid east at the top of a page or sheet, rather than north. An east-west baseline runs through the site maps (running top to bottom on a sheet) that establishes the grid coordinates. The Y-Axis number of a unit increases toward the east and decreases toward the west. The X-Axis is defined as left and right of the base with the prefix “L” or “R.” Thus a unit designation might be 645 L10 or 660 R 15. The unit coordinates refer to the upper left corner of a unit on a map, which corresponds to the northeast corner.

All features have been relabeled from an alphabetic system to a numeric system. Both designations are shown in the feature table. Features (posts, pits, etc.) typically were drawn in plan view on excavation cards. Profiles were not consistently recorded. They normally were portrayed if a feature yielded artifacts, or if an excavation unit wall bisected a feature.

The excavation forms do not indicate if the unit or feature soils were screened, although this was a common practice in the era in which the site was excavated. The small size of many of the artifacts suggests that screening was used for the 1960s excavations under the direction of William Jones. In the Context module of CMAP, Recovery Method has been entered as “Dry Screen”, and Screen Size has been entered as “Not Recorded.”

Soils were only generically described by color, often accompanied by a description of inclusions such as shell or charcoal: for example, “Black with broken shell.” These descriptions indicate that the upper 1 to 1.5 feet of soil throughout the excavated portion of the site was a dark midden with numerous shell fragments. The underlying subsoil is typically described as yellow.

Features (with original designation) from 1960’s Excavations

| Feature | Feature Type | Unit Corner |

| F1 (Pit A) | Pit | 600 L5 |

| F2 (Pit A) | Post | 640 L10 |

| F3 (Pit B) | Post | 640 L10 |

| F4 (PH A) | Post | 645 L10 |

| F5 (PH B) | Post | 645 L10 |

| F6 (PH C) | Post | 645 L10 |

| F7 (PH D) | Post | 645 L10 |

| F8 (Pit A 12-18) | Pit | 650 L10 |

| F9 | Post | 650 L35 |

| F10 | Post | 655 R5 |

| F11 | Ash pit | 650 L5 |

| F12 (Trench A) | Trench | 660 L15 |

| F13 | Pit | 660 L5 |

| F14 | Pit | 660 L5 |

| F15 | Post | 660 L10 |

| F16 | Post | 660 L15 |

| F17 | Post | 660 L20 |

| F18 | Post | 665 L10 |

| F19 | Post | 665 L10 |

| F20 | Post | 665 L10 |

| F21 (Post A) | Post | 665 L45 |

| F22 (Post B) | Post | 665 L45 |

| F23 (Post A) | Post | 665 L50 |

| F24 (Post B 18-24) | Post | 665 L 50 |

| F25 (Post C) | Post | 665 L50 |

| F26 | Post | 665 L55 |

| F27 (Post A) | Post | 670 L5 |

| F28 (Post B) | Post | 670 L5 |

| F29 (Post C) | Post | 670 L5 |

| F30 | Post | 670 L25 |

| F31 | Post | 670 R10 |

| F32 | Post | 670 R10 |

| F33 | Post | 670 R10 |

| F34 (Post A) | Post | 675 R15 |

| F35 (PH A) | Post | 675 R20 |