| Location: | St. Johns County, Florida |

|---|---|

| Occupation Dates: | 1586-1763 (as mission site); earliest date of pre-Spanish Timucua settlement unknown |

| Excavator(s): | Ed Chaney; James Cusick; Kathleen Deagan; Timothy Johnson; John W. Morris; Charles Spellman; Gifford Waters; Jack Winter |

| Dates excavated: | 1938 (Winter); 1951 (Spellman); 1976 (Deagan); 1985 (Deagan and Chaney); 1993 (Deagan and Cusick); 1994 (Deagan and Morris); 1997, 2000, 2001, 2009 (Deagan and Waters); 2014, 2015 (Waters); 2018, 2019 (Deagan and Johnson)) |

Overview

The Mission Nombre de Dios /La Leche Shrine site (8SJ34) is located St. Augustine, Florida near Hospital Creek. Established in the late 1500s by the Franciscan Order, Nombre de Dios is the oldest of the Florida missions and the only one to survive beyond 1706 in more or less its original location (Hann 1990:426). The entire mission complex of Nombre de Dios, which includes the church/chapel, other Spanish buildings, the surrounding Native American village would have spanned the current grounds of the Fountain of Youth Archaeological Park (8SJ31) and the current ground of Mission Nombre de Dios (8SJ34). Due to current ownership and property lines the two areas have been given different Florida Master Site File archaeological site numbers. The first Spanish church of Mission Nombre de Dios was built approximately 125 meters to the north of the 8SJ34 site. Over time the central area of the mission moved south to the present-day grounds of Mission Nombre de Dios. Some time during the In the early seventeenth-century, the La Leche Shrine was established at Nombre de Dios. Documents indicate it was represented by a venerated statue from Spain brought to Florida by the Franciscans (Gannon 2008). The shrine was the focus of much devotion among St. Augustine Catholics, especially women, and drew substantial offerings and alms (Deagan 2012:25). In 1677, Spanish Florida Governor Pablo de Hita y Salazar built a coquina church on the site to house the venerated image.

Throughout its history the Mission and Shrine site experienced two major destruction episodes. In 1702, La Leche church and the mission buildings were burned during the siege of St. Augustine by British South Carolina Governor James Moore. The church was subsequently rebuilt with coquina and and it is believed that at this time a tabby addition was constructed immediately to the west and attached to the church (Deagan 2019:60). After the end of the Yamasee War of 1715, some Yamasee Indians relocated to Nombre de Dios. British accounts around this time describe the mission as a “Yamasee strong town” (Deagan 2019:17), and in a 1723 census, two villages named Nombre de Dios are documented. This includes “Nombre de Dios Marcaris,”—the old Nombre de Dios containing the La Leche Shrine on the north bank of Hospital Creek—and “Nombre de Dios Chiquito” on the south bank (Deagan 2020:27).

In 1728, British Colonel James Palmer led a raid on St. Augustine, destroying Nombre de Dios Macaris and La Leche in the process. After Palmer’s raid, Governor Antonio de Benavides ordered the church and buildings at Nombre de Dios blown up to prevent their future use by enemies (Campen 1971: 37). By 1759, the area encompassing 8SJ34 had been totally abandoned and the two Nombre de Dios villages accounted for in the 1723 census combined to become one of two remaining Native towns in St. Augustine, Tolomoto and Nombre de Dios (at the location of Nombre de Dios Chiquito, south of the Hornabeque line). At the end of the First Spanish Period in 1763, the remaining Native Americans on the two missions left for Cuba with the Spanish.

The location of 8SJ34 became part of Governor James Grant’s farm during the British period (1764-1783) (Halbirt 1999). After Grant’s departure in 1771, the new Governor, Patrick Tonyn, allowed several Minorcan families to farm parts of the land, including parcels of 8SJ34 (Deagan 2012:29). One member of the Villalonga family built a small house on the north side of Hospital Creek, probably close to the Shrine. Farming activities continued on the site during Florida’s Spanish II (1784 to 1821) and Territorial (1822-1845) periods (Bagwell 1938).

In 1848, grievances over property taken by the United States in 1821 were presented to the United States Congress by the Catholic congregation in St. Augustine. One of the properties included the site of Mission Nombre de Dios/La Leche, described at the time as the “Episcopal church lot” (Gannon 1983:153). John McGuire sold the Nombre de Dios/La Leche property in 1868 for one dollar to Bishop Augustín Verot. Verot built a chapel on the site in 1875 after mistakenly believing a missionary had been martyred at Nombre de Dios (Bagwell 1939:7; Deagan 2020:14). Two years later the chapel built by Verot was destroyed by a hurricane. A second reconstruction of the chapel took place in 1914, which is the present standing chapel.

The site was also used as a Catholic cemetery at the end of the nineteenth century when Tolomoto cemetery became full following the yellow fever epidemic of 1884. Burials ceased on the site in 1892 after the Catholic cemetery San Lorenzo opened. Other modern developments on 8SJ34 include a gift shop, small office building, and rustic alter installed along the northwest corner during the 1930s. Today, the Nombre de Dios/La Leche site incorporates public history and has a museum which opened in conjunction with St. Augustine’s 445th anniversary in 2010.

Documentary Evidence

Nombre de Dios appears on mission lists and censuses created during visitations by Spanish administrators and friars (de las Alas 1602; Calderón 1675; Rivera 1717; Benevides 1726; Bullones 1728). In 1586, an account by Juan de Posada describes a Spanish-allied Christian Indian village around the area of what would later become the mission (de Posada 1586, cited in Quinn 1979:151). The following year, in 1587, the first full-time friar, Fray Alonso de Escobedo, was assigned to Nombre de Dios and oversaw the construction of the first church on the site (Geiger 1937:55; Hann 1994). At the time of Escobedo’s arrival, the Timucuan cacica (chief), Doña Ana, governed the mission village and was later succeeded by her daughter, Doña María. A 1602 testimonial by Alonso de Alas documents how Fray Balthazar López performed a mass baptism of 80 people at Nombre de Dios in 1595 (Arnade 1959:57; Shea 1886:153).

The Mestas map of 1593 places Nombre de Dios at about 1,500 pasos (paces, which is a variable width of about one meter) north of [?] the town of St. Augustine (Deagan 2012:22). Subsequent maps in 1606 and 1659 describe the mission about a quarter of a league (1 kilometer) distant from town (Geiger 1937:196; Juan de la Calle in Chatelaine 1941:123n12).

The mission population at Nombre de Dios fluctuated due to disease and attacks from the British and their Native American allies. In 1602, the mission’s vicar, Fray Pedro Bermejo, reported around 200 Natives living at the mission (Bermejo 1602). Four years later, a visit by Bishop Juan de las Cabeza de Altamirano documents 216 Natives and 20 Spaniards comprised of soldiers, fishermen, and hunters (Gannon 1983:46-47). By 1674, the mission population had sharply dropped with a visit by Bishop Gabriel Diaz Vara Calderon stating, “Going out of the city [of St. Augustine], at a half a league to the north there is small village of scarcely more than 30 Indian inhabitants, called Nombre de Dios” (Spellman 1965:368).

Native American refugees from other Spanish missions relocated to Nombre de Dios in the early eighteenth century (Bushnell 1994; Hann 1990:503). During Colonel James Palmer’s 1728 raid on St. Augustine, a British soldier purportedly took the figure of baby Jesus from La Chapel and presented it to Palmer. Palmer is said to have rebuked the sacrilegious act (Shea 1896:465). Shortly after Palmer’s attack, the settlement of Nombre de Dios Macaris was relocated to and combined with Nombre de Dios Chiquito, which was located south of Hospital Creek and the Hornabeque Line. Between 1738 and 1759, the Native population at Nombre de Dios dropped from 13 families to 11 families (Horscaistas 1738; Ruís 1759). Other accounts of Nombre de Dios/La Leche can be located in the works of archaeologists and historians that have studied the mission documents (Hann 1996; Milanich 1999; Worth 1988a, 1988b; Swanton 1922; Gannon 1983).

Excavation History, Procedure, and Methods

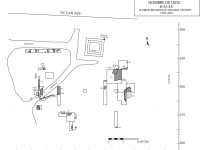

The first archaeological excavation at Nombre de Dios/ La Leche was conducted in 1938 by Mr. Jack Winter as part of the Carnegie Institute of Washington-sponsored study of Spanish defenses (Chatelaine 1941). Excavations focused on locating evidence of the first of nine wooden Spanish forts built before the Castillo de San Marcos (Cusick 1993:11-13). Around 115 feet of 3- and 4-foot-wide trenches were excavated. Fieldnotes for Winter’s excavations are sparse and do not mention the recovered artifact types and quantities. However, rough sketches of postmolds and pits were made based on the trenches excavated. Winter did not find evidence of the early Spanish fortification and the location of artifacts associated with his excavations are unknown.

In 1951, Father Charles Spellman, Director of the Diocese of St. Augustine Archives, conducted an excavation on the site. Spellman focused on locating the original stone chapel of Nuestra Señora de la Leche with the assistance of University of Florida students working under John Goggin (Spellman 1952; UFAL site file records). The initial excavation efforts consisted of eight units, and although no scale appears on the extant map or in the report, units appear to measure 5 feet by 5 feet (Deagan 2012:32). Spellman’s excavation uncovered the remains of a structure built of coquina block and tabby measuring at least 80 feet east to west and 35 feet north to south with possibly two or more rooms. Based on the initial findings, an additional 23 units were excavated. Recovery methods (e.g., screen size and materials saved versus discarded) are not mentioned in Spellman’s original report.

In 1976, a field school from Florida State University conducted a broadscale sub-surface survey of St. Augustine’s environs to locate colonial period sites. Kathleen Deagan directed the survey, which was executed on a 10-meter grid with the use of a 4” bit diameter power auger (Chaney 1986; Luccketti 1982). A total of 117 of auger tests were conducted on the site of 8SJ34. Thirty-eight of the tests yielded artifacts that were mostly Native American (87%) with concentrations of European (13%) artifacts along the southern end of the site (Deagan 2012:42).

General methods and protocols for subsequent excavations on 8SJ34 largely remain consistent. All naturally occurring soils were excavated in ten-centimeter levels with areas of soil discoloration or altered textured mapped, designated, recorded, and excavated separately (Deagan 2020:158-160). Excavated soil from unit levels was water screened through 1/4 inch mesh and soil from features water screened using 1/16 inch mesh. Recovered shell was weighed, recorded, and discarded from each provenience with a random sample bag of ca. 5 liters of whole and hinged shell retained.

In 1985, Ed Chaney, then a University of Florida graduate student, excavated three test units. Chaney attempted to tie in his excavations onto the existing grid at the adjacent Fountain of Youth Park site. Therefore, his grid designations do not correspond to those in subsequent excavations on the site (Deagan 2012:43). Two of Chaney’s units measure 1.5 x 3 meters. Time constraints led to a third unit only measuring 1 x 2 meters. Chaney’s unit locations were based on the 1976 survey results, and excavation goals centered on better understanding the site’s sixteenth-century components. One unit exposed a large trench, with postmolds, that Chaney interpreted as a possible sixteenth century ditch/moat with a supporting wall for a Spanish fort.

In 1993, James Cusick conducted excavations under the sponsorship of the University of Florida Institute for Early Contact Period Studies. The goal of the excavation was verifying the existence of a Spanish fort and locating other prospective areas for future excavations (Cusick 1993; field notebook, Nombre de Dios, 1985/1993:61-62). Three units were opened with variable measurements of 5 x 5 meters, 3 x 3 meters, and 1 x 2.2 meters. Cusick confirmed a sixteenth century, moat-like defensive feature (Cusick 1993), and one of the 3 x 3 units exposed a lime processing pit lined by burned logs. Later excavations in 1994 and 1997 determined the lime processing pit’s measurements to be 4.6 meters in diameter and 1.5 meters deep. Furthermore, radiocarbon dates from the burned logs indicate they were cut in the late fifteenth to early sixteenth centuries with associated artifacts suggesting an end-use date of 1600 (Deagan 2012: 86-87).

Additional University of Florida field schools in 1994, 1997, and 2001 turned to building on discoveries made in 1985 and 1993. The 1994 excavations used a combination of units (3 x 3 meters), test trenches, shovel testing, and an electromagnetic conductivity survey. Kathleen Deagan directed the fieldwork. Shovel tests and test trenches exposed additional areas of the ditch/moat, postmolds, and trash middens. The excavations associated with the moat-like feature uncovered its western terminus, and additional excavations focused on the presumed lime kiln (Morris 1995:14).

Excavations in 1997 were built around four goals. These included focusing on the wall trenches associated with the moat-like feature uncovered in previous excavations, gaining a better understanding of the lime processing pit documented in 1993, locating features associated with the sixteenth century, and recovering evidence for the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century mission (Waters 1998:6-7). A total of 39.5 square meters was excavated through a combination of units (two 3 x 3 meters, one 2 x 3 meters, two 1.5 x 3 meters, and one 1 x 3.5 meters), test trenches, and shovel tests. Further documentation on the moat-like feature in 1997 discovered a wall trench and associated postmolds running roughly north-south and perpendicular to the western terminus of the moat-like feature. Excavations roughly ten meters south of the moat-like feature revealed the presence of two very large postholes with postmolds dating to the sixteenth century, suggesting the presence of a former Spanish fort or blockhouse on the north end of the site (Waters 1998). Additionally, a posthole survey and an electromagnetic conductivity survey were conducted in a dirt parking area on the north side of Ocean Avenue. These surveys were conducted in an effort to determine if the moat-like feature might be present in the area, as well as to determine if there were any 16th century deposits present. This area of the site was designated as 8SJ34X to differentiate it from the main portion of the site. The posthole survey uncovered over 100 Native American ceramic sherds, less than ten fragments of majolica and olive jar combine, and a large amount of modern artifacts. The EM survey did not show any definitive evidence of a moat-like feature or other 16th century features (Curtis 1997).

Three 1 x 3 meter units were opened in 2001. Additional wall trenches were located during the excavation with depths ranging between 20cm to 30cm and widths from 30cm to 50cm. Additionally excavated in 2001 was a 12-meter long east-west oriented trench extending from 412N to 424E north of the moat-like feature. Five shallow, parallel linear stain features were identified in this trench and interpreted as possible sleeper sill logs for supporting a wall or earthwork (Deagan 2012:67).

In 2009, Kathleen Deagan and Gifford Waters directed excavations with the aim of assessing potential structures uncovered in previous excavations and exploring construction episodes of the standing chapel built by Bishop Verot. Six units were opened (three 1.5 x 3 meters, one 1.5 x 1.5 meters, and two 1 x 1 meters). Two building episodes were suggested for the standing chapel and include the 1875 construction by Verot and a 1914 reconstruction episode related to a restoration (Deagan 2012:106). Evidence of an older potential structure(s) was uncovered as well through the documentation of a dense shell layer with postmolds.

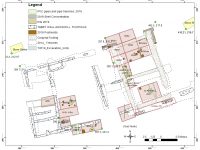

Excavations between 2011 and 2019 turned to defining the La Leche Shrine. In 2011, small exploratory trenches re-exposed portions of the coquina block structure documented by Spellman in 1951. Furthermore, the exploratory trenches documented a foundation footprint of a large structure around 85 feet east to west and 40 feet north to south (Deagan 2012:36). Identified as the La Leche Chapel, a unit (3 x 3 meters) placed near the center of the south wall of the exposed Chapel revealed further evidence of coquina construction and poured tabby.

The primary goal for excavations in 2014 was revealing the Chapel’s footprint from the extant walls. A 12cm deep wall trench (Feature 53) with irregularly placed posts along its side was found, and cultural material recovered in the trench date to after the destruction of the Shrine in 1728. This trench may be related to the Minocran farmer, Juan Villalonga, who built a home on the site during the British period (Deagan 2019:73).In the 2015 season, backfill from the 2014 excavations was removed to expose the Chapel’s foundation for public archaeology in celebration of St. Augustine’s 450th anniversary. Two 3-meter by 3-meter units were also opened inside the chapel to further define the structure. Based on the results of the work from 2011-2015 it was hypothesized that the coquina foundations represent Governor Pablo de Hita y Salazar’s church/chapel, and the tabby foundations were constructed after the church (most likely after the 1702 raid) and represent the foundations of a convento complex.

The 2018 field season focused on obtaining further insights on construction methods, architecture, chronology, and history for the chapel. Laser scanning and photogrammetry of the exposed foundations were completed during this process. Additional insights in 2018 included the documentation of a rubble layer (approximately 23-25cm thick) thought to be associated with the chapel’s 1728 destruction. Other finds include a rectangular space along the northwest corner of the probably convento that perhaps functioned as a storage, food preparation, refuse, or bathing space for convento residents (Deagan 2019:72; 2020:68-69).

In 2019, excavations focused on areas not yet excavated with the additional goal of obtaining proveniences dating over the course of the site’s occupational period. A large pit (Feature 79) was found under the west junction of the Shrine’s partition. Artifacts recovered in the pit date to the seventeenth century. Additional discoveries include confirming that the central patio area of the chapel was enclosed by tabby walls, a possible walkway or special function area, and a dense trash midden perhaps maintained through sweeping by convent residents.

Summary of Research and Analysis

The Nombre de Dios/La Leche site encompasses around 3 acres (1.2 hectares) and measures approximately 120 meters north and south and about 100 meters east and west. It should be noted that the first church of Mission Nombre de Dios was built approximately 125 meters to the north of the 8SJ34 site on the current grounds of the Fountain of Youth Archaeological Park. The entire mission complex, containing the church and other Spanish buildings along with the Native American village would have spanned both properties, but has been identified as two distinct archaeological sites based on modern property lines. Three zones have been assigned to the site based on its archaeological stratigraphy. Zone 1, the uppermost layer, is modern with disturbed cultural affiliation due to frequent disturbances on the grounds since the mid-1980s. Zone 2 dates to the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and is associated with mission period activities and the La Leche shrine. Zone 3 is comprised of both pre- and post-European contact deposits up to the sixteenth century.

Archaeological research on 8SJ34 has focused extensively on the northeastern corner of the site and south of the standing La Leche chapel built by Bishop Verot in the late nineteenth century. Excavations have revealed the probable location of the Nombre de Dios mission and Nuestra Señora de La Leche Shrine convent complex. Other structural elements documented through potmolds and wall trenches perhaps relate to early Spanish fortifications such as a ditch, a possible palisade, a sixteenth century lookout tower or blockhouse, and a possible seventeenth century structure . A limeprocessing pit built by the Spanish and abandoned in the late sixteenth to early seventeenth century has also been identified.

Artifacts recovered on the site reveal information regarding Native occupants, the mission settlement, and Spanish/European activitiesat this mission and shrine complex. Trash pits and sheet deposits predating the construction of the shrine exhibit a large presence of Native pottery; approximately 92% of all colonial artifacts recovered on 8SJ34 are Native American (Deagan 2012:113). Despite of the extensive shell midden deposit on the site, only a few midden deposits have been attributed to a pre-1565 Timucuan population. The largest and most puzzling feature to date is moat-like feature. Approximately four meters wide and 70cm deep, this feature is aligned from the southwest to northeast at an angle roughly 70 degrees east of north. Artifacts recovered from the ditch/moat indicate it was abandoned and filled in the early seventeenth century with a construction period sometime between 1565 and its filling. Other architectural finds include several narrow linear trenches. Identified as potential log sleeper sills, they are similar in form to others found at the adjacent Fountain of Youth Park site (8SJ31). However, these narrow trenches do not conform to the SW-NE orientation of the ditch/moat but rather align due north to south (Deagan 2012:134-135).

Timucuan St. John’s pottery represents the main pottery type at the Mission site until after the seventeenth century. In the mid-to-late seventeenth century, other Native groups, such as the Guale, Yamasee, and Apalachee, relocated in and around St. Augustine. This relocation brought other pottery traditions to the area such as San Marcos. Associated with the Guale from coastal Georgia, San Marcos is the second most prevalent pottery type from 8SJ34 during the site’s early Mission period. European artifacts have been recovered in lesser amounts on the site and include pottery, personal adornments, weaponry, glass, architectural items, and tools.

Archaeology has uncovered the footprint of the original coquina chapel and La Leche Shrine built during the seventeenth century. While documentary evidence states that the chapel or shrine was ornately decorated with murals, the only archaeological evidence regarding its decoration is the recovery of fragments of white-washed lime plaster and broken coquina pieces with red paint. Archaeological evidence supports the hypothesis that the coquina foundations represent the church/chapel built by Governor Pablo de Hita y Salazar in 1687 and the tabby remains represent the subsequent construction of an attached convento, most likely built after the 1702 destruction of the chapel (Deagan 2019:34-35).

Sixty percent of the artifacts recovered on the Chapel/Shrine complex is native pottery. Of these, 28% is San Marcos and 4% is St. Johns. This contrasts with earlier periods where St. Johns pottery makes up the bulk of recovered native pottery on 8SJ34. The current interpretation is that a sparse population of Guale may have been the primary occupants of the location prior to the construction of the La Leche Shrine (Deagan 2020:84). Mexican-origin majolica makes up most of the European pottery on the Shrine site with Puebla Blue on White and San Augustín Blue on White the most numerous types recovered. Although two British military assaults were made on the Shrine in the eighteenth century, very few items related to weaponry have been found, with the most direct evidence being the recovery of two cannon ball fragments and twelve lead shot (Deagan 2020:95). Relatively few colonial period artifacts dating to after the Shrine’s destruction in 1728 have been recovered.

Gifford Waters and Charles Cobb

Florida Museum of Natural History

University of Florida, Gainesville, FL

July 2023

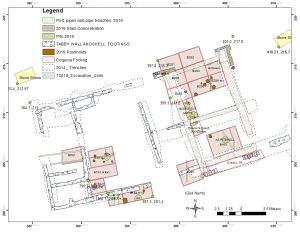

Site Grid

A modified Chicago grid system has been used to maintain horizonal control at the Mission Nombre de Dios/La Leche Shrine site since 1985, with excavation units designated by the grid coordinate of their southwestern corner and measured in meters. This grid was reestablished each field season using known permanent datum points located on the site. Vertical control has been maintained using a fixed datum plane established with a transit or level, with each excavation seasons vertical datum being recorded in relation to manhole covers on Ocean Avenue. . Vertical measurements are recorded as meters below datum (mbd).

Excavation and Recovery Methods

Beginning with the 1985 excavations, all naturally occurring soils were excavated in 10-centimeter levels (unless otherwise noted). Excavation units typically measure 1 x 1 meter, 1.5 x 3 meters, or 3 x 3 meters. A 15cm baulk was left around each unit during the 1985 field season and a 10cm baulk was left in place for all subsequent field seasons.

Soil from proveniences was water screened through 1/4” mesh, and soil from Features and Areas (see below for definitions of provenience types) were further water screened through 1/16” mesh. Artifacts recovered on site were separated into cultural material, building material, charcoal, faunal remains and shell, and then bagged and labeled separately.

One liter soil samples were taken from each provenience during the 1985 field season. During the 1997 season, 5-liter soil samples were taken from each provenience. In cases where the provenience totaled less than 5-liters, a decision was made to either keep all the soil or screen it all. Soil samples taken from 1994 to 1997 were further processed using flotation separation and include 1-liter archived samples for the 1997 season. Soil samples after 1997 were standardized at 2-liters and wet-screened through a series of graduated step screens of .25” (6.3mm), .125” (3.17mm), .0234” (.594mm), and .0165” (.419mm).

Shell recovered from each provenience was weighed, recorded, and discarded after a random sample of one large bag of whole and hinged shells was taken.

Unless otherwise noted, units were excavated to culturally sterile soil. All areas of soil discoloration or altered texture were mapped, designated, recorded, and excavated separately. Sketch maps of units at various points during excavation were taken, and records of when a unit was photographed, mapped, and profiled were documented along with relevant comments. All photographs taken were provided a photographic log (PL) number, which followed consecutively after the 1994 excavations. These contain the subject, date, and grid designation. Until 2002, black and white as well as color slide photos were taken on site. Since that date, images have been taken with digital cameras.

Stratigraphic records (SR) were completed after each unit was fully excavated. All four walls of each unit were drawn unless otherwise noted, and each SR was given a consecutive number following those of the previous field season.

Stratigraphy

The following nomenclature was assigned to the soil horizons:

- Zone 1 (Z1): Very dark grey to black sandy soil, with small shell fragments, shell hash, and root disturbance. It is directly under, and is disturbed by, the sod layer. This zone contains mixed cultural material from the 16th through 20th centuries.

- Zone 2 (Z2): Very dark brownish grey, sandy soil with heavy whole and crushed shell content. This zone is associated with the 17th and 18th century mission occupation.

- Zone 3 (Z3): Light yellowish brown mottled soil of sandy consistency with little or no shell content. This zone is associated with the prehistoric and 16th century occupations at the site.

Field Designations

The following nomenclature was assigned to the excavated deposits:

Field Specimen # (FS): a unique number assigned to each excavated provenience. The sequence of field specimen numbers continues for each year’s excavation from the previous field season. Proveniences are designated as one of the following categories:

- Zone (Z): a naturally occurring deposit or non-intrusive sheet midden that covers the entire site or large portions of it.

- Level (L): an arbitrary 5-centimeter or 10-centimeter increment of soil within a naturally occurring deposit.

- Area (A): an amorphous soil discoloration or intrusion into the soil matrix of a unit. These areas could not be confidently identified as cultural in origin and were given consecutive numbers within each unit.

- Feature (F): a deposit that was known or suspected to be the result of human activity and possessing an identifiable function. Feature numbers were carried over from the previous field seasons and new features that were discovered were given the next consecutive site-wide feature number.

- Postmold (PM): a stain resulting from the deterioration of a post, often expressed in plan view as a circular stain. Postmolds were numbered consecutively within each unit. Postmolds were pedestaled and then vertically sectioned and drawn in cross section and the soil associated with the postmold was retained for screening and analysis.

- Possible Postmold (PPM): a deposit that could not be confidently identified as a post mold, but displayed the outline of a circular stain in plan view. Possible postmolds were generally treated like postmolds in terms of pedestaling and vertical sections. “Possible postmold” and “Postmold” designations were often used interchangeably.

- Posthole (PH): the area surrounding a postmold of the hole into which a post was placed. Postholes were also numbered consecutively within each unit. Postholes were excavated in the same manner as postmolds. (In instances where a postmold was visible within a posthole the two deposits were recorded, mapped, and excavated separately.)

Laboratory Analysis

Artifacts recovered between 1985 and 2019 were analyzed using standard identification and recording protocols. Information gathered during this process was used to establish the terminus post quem (TPQ) of each provenience, which was then used, in conjunction with the stratigraphy to establish its period of cultural affiliation. Charcoal, faunal, and shell samples were weighed and recorded during laboratory processing, if they had not already been recorded in the field.

Records

Field records for the site are extremely limited for the 1938 and 1951 excavations. Field notebooks (1985-2015) housed at the Florida Museum of Natural History document procedures, sketches, and thoughts by the field supervisor. Other records include plan view and profile maps of units, color slides, black-and-white prints of the excavations, digital photographs, and photogrammetry of the exposed foundation of the La Leche Chapel.

| Features Associated with a Ditch/Moat with Possible Supportive Wall/Palisade | ||

| Feature | Feature Type | Unit Corner |

| F3 | Trench with Postmolds | 287N 442E |

| F4 | Moat-like Ditch | 281N 436E |

| F9 | Moat-like Ditch | 277N 419E |

| F12 | Moat-like Ditch | 275.75N 413.05E |

| F22 | Moat-like Ditch | 277N 411E |

| F23 | Wall Trench/Mud Sleeper | 280N 412.5E |

| F23N | Wall Trench/Mud Sleeper | 277N 411E and 280N 412.5E |

| F23S | Wall Trench/Mud Sleeper | 277N 411E |

| Post and Wall Trench Complex and Related Features | ||

| Feature | Feature Type | Unit Corner |

| F19 | Wall Trench | 268N 422E |

| F19N | Posthole | 268N 422E |

| F19S | Posthole | 268N 422E |

| F21 | Pit | 268N 422E |

| F25 | Posthole | 264.5N 423E |

| F32 | Possible Posthole and Postmold | 263N 419E |

| F33 | Possible Posthole fill | 268N 417.5E |

| F33W | Possible Posthole fill | 268N 416.5E |

| F34/34W | Possible Posthole fill | 260N 424E |

| F38 | Possible Posthole fill | 271N 425E |

| Chapel/Shrine and Convento/Hermitage Complex | ||

| Feature | Feature Type | Unit Corner |

| F36 | Coquina, West Wall | PT 2, Sec. 1-2 |

| F39 | Shell and Mortar concentration | 203N 401E |

| F37 | Coquina, South Wall | S. Wall Trench |

| F40 | Mortar concentration | 203N 401E |

| F41 | Shell Mortar, West Wall | W. Wall Trench |

| F42 | Coquina, North Wall | N. Wall Trench W., Sec. 2-3 |

| F43 | Shell Footing, East Wall, South ½ | PT 1, Sec. 1-2 |

| F44 | Coquina, Mortar Shell, North Partition Wall | PT 3, Sec. 1E-W |

| F46 | Shell Footing, East Wall, North ½ | PT 1N, Sec. 3 |

| F47 | Coquina, West Wall Extension/Partition | PT 5, Sec. 1-3 |

| F48 | Tabby Floor, South Room | PT 6, Sec. 1-2 |

| F49 | Coquina Wall Footing, Center of the East Wall | PT 8, Sec. 1-3 |

| F50 | Tabby Wall, East/West Partition | PT 6, Sec. 1-2 |

| F52N | Tabby Wall, West | PT 10, Sec. 1-2 |

| F52S | Tabby Wall, West | PT 9, Sec. 1 |

| F53 | Wall Trench with Postmolds | PT 11, Sec. 1 |

| F55 | Coquina Wall, Rubble (South) | 199.39N 306.32E |

| F58 | Charcoal Pit | 203.5N 388.8E |

| F64 | Pit | 203.5N 388.8E |

| F65 | Possible Storage Area | 211N 390E |

| F66 | Trench, Rubble Fill | 200N 405E |

| Features Underlying the Coquina Building and Tabby Addition | ||

| Feature | Feature Type | Unit Corner |

| F72 | Shell Deposit | 202.2N 391.8E |

| F77 | Pit, Trash | 205.5N 392E |

| F79 | Pit, Trash | 210.4N 401E |

| Features Not Assigned to Groups | ||

| Feature | Feature Type | Unit Corner |

| F5 | Lime Processing Pit | 278N 439.5E and 278N 442.5E |

| F7 | Midden, Trash | 276N 435E |

| F8 | Midden, Shell with Possible Postmold | 279N 435E |

| F10 | Postmold | 278N 428E |

| F10B | Possible Postmold | 278N 428E |

| F11 | Stain (w/ shell and charcoal) | 273.5N 419E |

| F13 | Midden, Shell | 273.5N 419E |

| F18 | Midden, Shell with Posthole | 283N 415E |

| F20 | Midden, Shell | 277N 411E |

| F24 | Midden, Shell | 264.5N 423E |

| F26 | Possible living surface | 292N 408E and 292N 411E |

| F27 | Midden, Shell | 292N 408E and 292N 411E |

| F28 | Pit | 292N 411E and 292N 414E |

| F29 | Midden, Shell | 272N 412E |

| F30 | Possible living surface | 292N 417E |

| F31 | Midden, Shell | 263N 419E |

| F35 | Midden, Shell | 271N 425E |