| Location: | Suwannee County, Florida |

|---|---|

| Occupation Dates: | 1610 (?) to 1656 as a mission site; earliest Timucua occupation unknown |

| Excavator(s): | Jill Loucks; Jerald Milanich |

| Dates excavated: | 1976 (Milanch); 1978 (Loucks) |

Overview

The Baptizing Spring site (8SU65) is situated on the east side of the Suwannee River approximately two miles from the town of Luraville in Suwannee County. The site gets its name from a spring-fed sinkhole located at the site (Milanich 1999:14). Initially, the site was thought to be associated with the seventeenth-century mission San Agustin de Urica (ca. 1610-1656), which is one of a handful of initial missions established by the Spanish in La Florida during the first decade of the 1600s (Loucks 1993:195). However, research by historian John Hann and archaeologist John Worth indicates that the mission at the site was likely San Juan de Guacara (ca.1610-1657), located in Utina (Timucuan) Indian territory. This was one of four missions along the Suwannee River that made up the Utina Timucuan province (Hann 1990:470; Worth 1998a:68). All were abandoned around 1656 as a result of the Timucua rebellion.

The Baptizing Spring site was first identified in 1976 during the establishment of a pine plantation by Owens-Illinois, Inc. Jerald Milanich of the Florida Museum of Natural History conducted a brief, 10-day excavation that year, focusing on two presumed Spanish building locations. Jill Loucks (1978) followed in 1977 with a survey of the surrounding area that identified six sites in a 500 meter radius of the mission, five of which possibly were contemporaneous with the mission. Charles Fairbanks at the University of Florida next obtained funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities to further explore the mission in 1978. The fieldwork was conducted by Jill Loucks and represented the first formal, comparative study of both Spanish and Native American structures at a Florida Franciscan mission.

Louck’s study of two Spanish structures and two Native American structures was the source of her dissertation and a related publication (Loucks 1979, 1993). The European buildings likely represent the mission’s church and convento, whereas the Native American structures appear to have been domiciles.

Documentary Evidence

In the beginning of the seventeenth century, a handful of friars arrived in La Florida from Spain to establish a mission system for converting the native populations. The friars’ efforts resulted in a moderate compilation of documents describing their endeavors involving many of the Indian groups occupying Florida and Georgia at the time. Because many of these documents (e.g., censuses, letters, and petitions) mention the Guacara mission, some information pertaining to the Native Americans and Spanish who occupied the site is available. The paper trail suggests that the friars likely established Guacara in the Utina Indian territory about 1610, making it one of the earliest operating missions in what the Spanish referred to as the Timucuan province (Worth 1998a:65). The mission remained at that location until approximately 1657, when it was abandoned after the Utina Indians at Guacara took part in the 1656 Timucuan revolt against the Spanish, evidently suffering greatly (Hann 1990:462). The following year, the mission moved from the Baptizing Spring site to Charles Spring, located two leagues to the west, also on the Suwannee River (Worth 1998b:175).

Excavation History, Procedure, and Methods

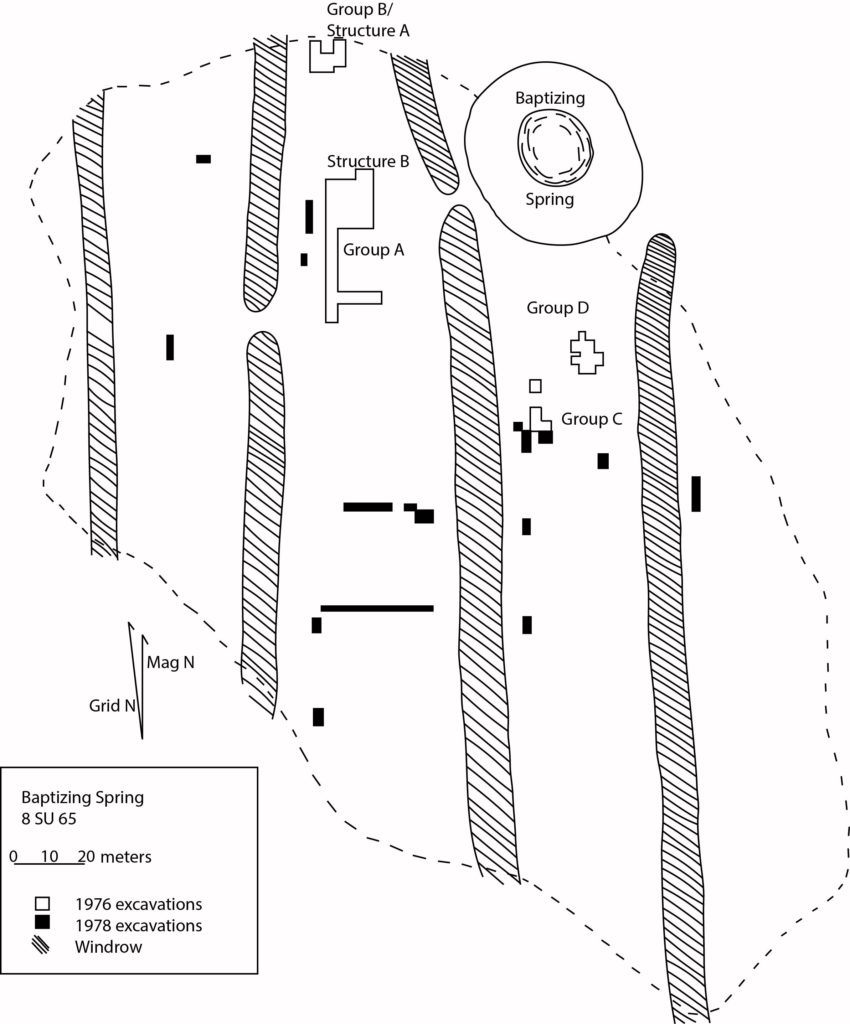

Initial excavations at Baptizing Spring began in 1976 with a brief University of Florida archaeological field school under the direction of Dr. Jerald Milanich. Over a ten-day period, sampling delineated rough boundaries of the site in an area of approximately 2.83 ha (Loucks 1979:118-119; 1993:196). The 1976 excavations totaled 346 square meters of four arbitrary sections of the site: Groups A, B, C, (each defined by feature clusters) and a fourth area containing two two-meter wide trenches. Subsequent work by Jill Loucks in 1978 led to the excavation of another 197 square meters of the site. This led to the delineation of a Group D feature cluster. Her investigations also included the placement of a number of one-meter-wide test trenches throughout the site to gain additional information on the spatial organization of the mission and village. The additional sampling focused on artifact concentrations dispersed across the site.

Groups A and B coincided with what appear to be individual square or rectangular structures associated with the Spanish mission complex. Post features and daub indicated the building in Group A (somewhat confusingly referred to as Structure B) measured 10 x 8 meters and had a packed red clay floor. The building in Group B (Structure A) measured 7 x 7.5 meters. Structure B seems to have been the church and Structure A the convento. Evidence of charred posts and wood in association with the church suggests that at some point the structure burned.

The extended excavations of Group C revealed a cluster of posts partially outlining two probable Native American structures (C and D) along with various features such as smudge pits, hearths, and storage pits (Loucks 1979:130, 139; Loucks 1993:202). The shape of Structure C could not be determined due to the complexity of overlapping posts. Structure D, represented by five postmolds, was also of indeterminate shape although the house was likely about 6 m in diameter. Despite the difficulty in delineating walls, Loucks (1979:193) believed that she had excavated most of the floor area of each of the structures.

Approximately 35 features interior and exterior to the likely structures were identified. Features within Structure C consisted of two hearths, smudge pits, and other types of pits used for trash and storage. Structure D contained various interior storage and indeterminate pits, as well as a partially articulated pig skeleton. Exterior features near the Native structures included a clay lined pit and pits used for trash and storage (Loucks 1979:139-146). Artifacts found in Structures C and D were mainly Native American, and were dominated by lithics and ceramics. Recovered European artifacts included olive jar and majolica sherds, ornamental objects such as a glass and copper beads, and a religious medal. Most of the European ornamental objects were associated with Structure D (Loucks 1979:281-288).

Investigations also set out to locate a possible cemetery associated with the mission involving 180 test pits and a test trench north of Group B, which yielded inconclusive results.

Summary of Research and Analysis

Excavations at the Baptizing Spring site in 1976 and 1978 revealed structural remains in the form of postmolds and post holes, pottery, and artifacts representing a community with both Spanish and Native American occupations. Spanish and Indigenous cultural materials included stone tool remains (e.g., debitage, projectile points), ceramics, beads and other ornamental objects, gunflints, nails, and miscellaneous metal fragments. Artifacts associated with Structure A included mainly Spanish ceramics such as olive jar and majolica, as well as a moderate amount of Indian pottery. Only a small number of ceramics, mostly Spanish, came from Structure B, although this area yielded a number of iron nails and spikes. Some of the features associated with the Spanish structures showed evidence of heavy disturbances from 19th and 20th century activities such as clearing and stump removal. The development of a pine plantation in this locality was associated with a series of windrows across the site, causing further damage.

Despite the post-occupational impacts to the mission, the structural evidence at Baptizing Spring offers some clues about the settlement arrangement of the mission town. Spanish Structure A (convento) is approximately 30 m NNW of Structure B (church). Structure B, the largest of the Spanish buildings, stood on the highest point of the town, which possibly bordered a central plaza.

The Indigenous houses C and D are each located about 80 m from the church, Structure C to the south and Structure D to the ESE. Structures C and D are approximately 20-30 m apart from one another (Loucks 1979:149; 1993:202). While most of the artifacts associated with the structures were Indigenous in origin, a small number of European objects, such as glass beads and a Catholic medal, were also recovered. The area just south of Structure B had a very low artifact density, possibly indicative of a plaza.

Two additional tested areas in the presumed Native American village portion of the site provided possible evidence for structures, or at least activity areas. Trench No. 2, 30 m southwest of Structure C, located two postholes and a large clay-lined pit with abundant artifacts. Trench No. 1, about 24 m SSW of Trench No. 2, encountered a cluster of postholes and pits.

The Native ceramic assemblage was characterized by a considerable degree of heterogeneity, including types associated with other regions (e.g., Chattahoochee Brushed and Ocmulgee Fields Incised, which are typical of the lower Chattahoochee drainage between Alabama and Georgia). It is not clear whether these represent imported vessels or the presence of immigrants.

Although floral and faunal samples were small, they suggested a strong continuity with pre-European contact subsistence patterns.

Five of the six sites located by Loucks as part of her local survey had ceramics of the late prehistoric and possible mission periods. Olive jar sherds were recovered from two of those sites, and a majolica sherd was found at one of those two sites. Loucks hypothesized that these habitations may have represented outlying communities that were still articulated with the mission complex in some manner.

Gifford Waters and Charles Cobb

Florida Museum of Natural History

University of Florida, Gainesville, FL

August 2019

Both the 1976 and 1978 field seasons used the same grid system. The site datum was arbitrarily set at 500N 500E at a point about 40 m west of the spring. This datum plane was calculated as 17.6 meters above mean sea level, and 2.4 meters above the ground surface at 500N 537E. All excavation units were designated relative to the datum by a southwest corner stake given in meters north and meters east. An arbitrary grid north was established 9 degrees and 10 minutes west of magnetic north in order to parallel the windrows created for the pine plantation.

Units were excavated in 10 cm arbitrary levels within natural strata until either encountering sterile subsoil or reaching a significant decrease in artifacts (< 10 in a level). Screening methods varied widely by context and by field season. In 1976 excavation unit soils from Structures A and C were passed through 3/8” x 3/4” diamond mesh with mechanical shakers. However, the feature soils in Structure C were either screened with 1/8” mesh or carefully troweled.

In 1978 most excavated soil was screened by mechanical sifters through a ¼” mesh. The one exception occurred when the mechanical screens failed and portions of Trench No. 1 and all of Trench No. 6 were hand-sifted through 3/8” x ¾” diamond mesh. In the analytical phase of the project, the soil from five features that had been bagged in the field was water screened through 1/16” mesh.

| Features Associated with Structure A | |||||

| Feature | Feature Type | Unit Corner | |||

| F11 | Clay-lined Pit | 539N 503E | |||

| F12 | Central Hearth | 542N 500E | |||

| Features Associated with Structure B | |||||

| Feature | Feature Type | Unit Corner | |||

| F7 | Red Clay Filled Pit | 503N 506E | |||

| F10 | Red Clay Filled Pit | 503N 503E | |||

| Features Associated with Structure C | |||||

| Feature | Feature Type | Unit Corner | |||

| F5 | Circular Pit (overlapping F6) | 443N 551E | |||

| F6 | Circular Pit (overlapping F5) | 443N 551E | |||

| F13 | Rectangular Smudge Pit | 440N 549E | |||

| F14A | Circular Fire Pit | 440N 549E | |||

| F14B | Circular Fire Pit | 440N 549E | |||

| F15 | Rectangular Smudge Pit | 440N 549E | |||

| F18 | Probable Storage Pit | 443N 547E | |||

| Features Associated with Structure D | |||||

| Feature | Feature Type | Unit Corner | |||

| F16 | Rectangular Pit | 464N 567E | |||

| F17 | Large Storage Pit | 464N 565E | |||

| F19 | Pig Carcass | 461N 565E | |||

| Trench 1 | |||||

| Feature | Feature Type | Unit Corner | |||

| F21 | Ovoid to Rectangular Trash Pit | 397N 509E | |||

| Trench 2 | |||||

| Feature | Feature Type | Unit Corner | |||

| F20 | Clay-lined Pit | 419N 521E; 419N 523E | |||

| Features Not Assigned to Groups | |||||

| Feature | Feature Type | Unit Corner | |||

| F1 | Puddling Pit | 500N 503E | |||

| F2 | Clay-lined Rectangular Basin | 497N 509E | |||

| F3 | Clay-lined Rectangular Basin | 500N 509E | |||

| F4 | Clay-lined Rectangular Basin | 497N 500E | |||

| F8 | Clay-lined Rectangular Basin | 509N 506E | |||

| F9 | Clay-lined Rectangular Basin | 506N 503E | |||